M.V.S. Ratnavale’s catalogue of classical Tamil works is a worthy tribute to the language

Though technology has made it easier to research ideas and let the mind wander down the lanes of a world where the writer is God, it has become harder to write prose or poetry that could be called a timeless classic.

At a time when nearly every word has a loaded significance due to the polarisation of discourse, lovers of classical writing can welcome a compendium titled English Catalogue of Ancient Tamil Literature (Palantamizh Ilakkiya Thoguppu).

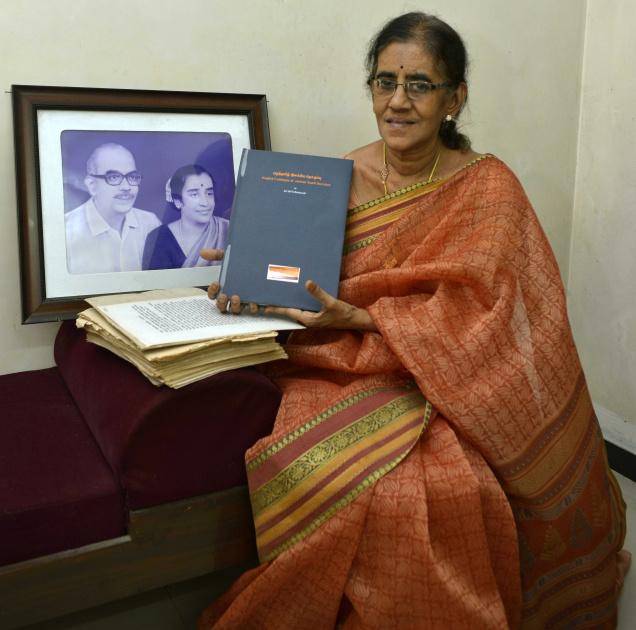

The editor of the tome is M.V.S. Ratnavale, (1915-1994), who has meticulously recorded 687 works of Tamil poets from 1000 BC (pre- to post-Sangam period). “My father had no reason to write his book except for his love of Tamil language,” says Sivasundari Bose, who finally put together the tome as a souvenir to celebrate Mr. Ratnavale’s birth centenary on December 25, 2015.

Bringing the 600 loose typewritten sheets into a modern book format was in itself a challenging task, says Ms. Sivasundari, a Tiruchi-based author who writes in English and Tamil.

“Outsourcing the typing work to data entry operators was not a good idea, because those who know accurate Tamil typing are hard to find,” says Ms. Sivasundari.

Born in Tuticorin into a family of 11 children, Mr. Ratnavale was the seventh child of M. V. Shanmugavel Nadar, the founder-chairman of Tamilnad Mercantile Bank. “His father died young, but my grandmother made sure that all the children were educated,” recalls Ms. Sivasundari. Mr. Ratnavale studied History in Presidency College, Chennai and American College in Madurai.

“He was always interested in doing something more than just earning a living,” says Ms. Sivasundari.

It was this desire to live differently that led him to start cultivating cardamom on the wild forest slopes of the Western Ghats in his estate ‘Kaantha Paarai.’

Besides collecting books in English and Tamil, his days were consumed by a passion for numismatics, philately and photography.

He won a national-level bronze medal for his extensive collection of Indian and British Commonwealth stamps.

After a peripatetic life, and the marriages of his four children, Mr. Ratnavale chose to settle down in Kallidaikurichi, Tirunelveli district, near the foothills of his estate. “Though my father wasn’t from a literary family, he had developed a taste for Tamil literature, and was equally fluent in English. He used to buy a lot of old books which he thought had to be shared with the world. And he felt the sharing would be best done in English, to reach out to a wider audience,” says Ms. Sivasundari. “That’s when he started taking notes.”

For over 20 years, Mr. Ratnavale tracked down the works for his catalogue, and kept saving his work on loose sheets of translucent paper.

“He had time, but he also worked very hard,” says Ms. Sivasundari. “He’d be at his writing desk at 9 a.m. and work till lunch. There’d be a short break, and he’d go back to the manuscript in the evening,” she adds.

Operating in a pre-internet era in a village where there was nobody he could share his work with or seek assistance from, Mr. Ratnavale’s catalogue, which begins at Aadai Nool and ends at Yellathi, is an example of meticulous research and physical effort.

“Each entry had to be typed correctly, and corrections had to be made immediately. It is so easy to delete or correct sentences on the computer. But I didn’t realise then what he was doing. Now I see the manual and intellectual effort he had put in to compile the book,” says Ms. Sivasundari.

After he completed his manuscript, Mr. Ratnavale faced the hurdle common to most first-time authors: finding a publisher. “Up until his 80s, he used to visit me in Tiruchi and go looking for publishers, but nobody was interested,” says Ms. Sivasundari.

The catalogue has managed to unearth works of greater literary and thematic depth than the ones that have held sway over popular imagination. “We all know Silapathigaram, or Thirukkural or Kamba Ramayanam, but there are others that we haven’t even heard of which are listed in this catalogue,” says Ms. Sivasundari. “Perhaps the lack of annotated texts or ‘urai’ to explain the lingo prevalent at that time could be a reason why they are forgotten now,” she adds.

Treatises on the need for harmony in music (Isai Nunukkam by Sihandi, 6th century), geriatric medicine (Moopu Choothiram composed by Ambihaananthar, 8th century) and an exhaustive Tamil Thesaurus (Pingala Nigandu by Pingala Muniver, 8th century) are among the little-known texts that are listed out in the catalogue.

Mr. Ratnavale has also added his own notes on various works to make it more reader-friendly.

Information from palm-leaf scripts suggests that the poetry of this era was not just about divinity or royalty, but also accounts of daily life, the performing arts, and mercantile activity that saw Tamil traders sailing to ancient Ur and Rome.

Publishing the book posthumously has made his family happy, but the book deserves to be more widely read, feels Ms. Sivasundari. “Ideally it should be available in university libraries as a key reference work. Tamil is like a treasure chest to some of us. It has a history going back thousands of years, and we should hold on to it because it is a way of life,” she says.

* * *

A life less ordinary

“My father was very liberal with me,” says Ms. Sivasundari Bose, an attitude she attributes to Mr. M.V.S. Ratnavale’s own childhood spent in an extended family that included not just his 11 siblings, but also cousins and relatives. “Children growing up in big families don’t judge others harshly,” she reasons.

Her own upbringing was marked by open style of parenting, says Ms. Sivasundari. “I was taught everything that my three brothers were taught,” she says. “My father never said ‘you are a girl and you shouldn’t do this.’ So I used to cycle to school, which was considered radical in those days. And because of the wild animals on the estate, I was also taught how to use a gun.”

Her mother introduced her to lessons in music and dance. “Nothing was forced on us, but we were always told where the limits lay.”

Ms. Sivasundari is the author of Golden Stag, a trans-generational saga about a community in Tamil Nadu that was published in 2006. In addition to this, she has translated Sangam-era love poems, and also written books in Tamil on more contemporary themes.

* * *

Gems from the catalogue

Some of the rare works listed by Mr. Ratnavale:

– Koothu Nool by Cheyitriyanaar, 6th century, explains theory of dance and drama

– Manthira Nool by Putkaranaar, 6th century, on mystic theology

– Thaala Samuthiram by Bharata Choodamani, 8th century, on the importance of beat in music

– Kaasiyappa Silpam by Pattinathu Adigal highlights excellence in sculpture in 10th century

– Thiraavaaham Ennooru by Macha Muni, 14th century, about science of metallurgy and alchemy

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Features> MetroPlus / Nahla Nainar / April 15th, 2016