Remembered at commemorations in Madras recently were two contrasting Gandhians. One, a man whose family I knew better than him, the other, I confess with regret, I had not even heard of. Of both I learnt so much subsequently, that two items in a column seem pitifully inadequate. If you hear about them again from me it will be because there are so many stories to tell about Dr Chandran Devanesen and Mahakavi Bala Bharathi Sankagiri Duraisamy Subramania Yogiar.

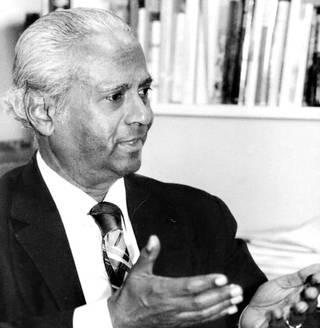

Both were sons of scholars. Chandran Devanesen was the first professor at Madras Christian College who was the son of an earlier academic there, David William Devanesen, a Professor of Biology who later retired as Assistant Director of Fisheries. Devanesan Senior wrote prolificly on subjects ranging from oysters to Vedanayagam Sastriar, the evangelist poet of Tanjore.

Yogiar’s father Duraisamy, fluent in Hindi, Persian and Urdu, lectured on the Holy Koran in English. Both imbued their sons with a yearning for knowledge and sharing it.

The institution builder

As the first Indian Principal of MCC, Chandran Devanesen is known for successfully transforming an institution influenced by Scots to one more Indian. But that exercise is not my focus. What is, is the little remembered founding of the North-Eastern Hill University in 1973. Starting from scratch in territory he knew little about, Devanesen developed in Shillong an institution to serve Meghalaya, Nagaland, Mizoram and, for a while, Arunachal Pradesh. He spent a year boning up on the Northeast before heading to it as Vice-Chancellor, but what he remembered best of that time was meeting this Central University’s Chancellor, Indira Gandhi, before leaving for his new home. The Prime Minister told him she trusted his vision and leadership on academic development, but “I can advise you on the tribal dynamics of the Northeast and its diversity.” He learnt more about the area in that one hour with her than in the year spent in libraries, he was to later recall.

The first Chair he established there was the Mahatma Gandhi Visiting Professorship, the second the Dr Verrier Elwin Chair, remembering that expert on the tribes of much of India. From early in life Devanesen was interested in Gandhi. His doctoral thesis, titled ‘The Making of the Mahatma’, focussed on the first 40 years of Gandhi’s life. The thesis was dedicated to two ardent disciples of Gandhi, Devanesen’s uncles, J(oseph) C and (Benjamin) Bharathan Kumarappa, from the Cornelius family of Tanjore.

Another significant Devanesen creation was the Estuarine Biological Laboratory by Pulicat Lake he helped Dr Sanjeeva Raj to set up. Devanesen did not live to see it come to naught in the new Millennium when Lake and surroundings, including environmentally sensitive islands, were despoiled by modern development. When he was alive he’d visit the Lab regularly with his family on weekends and return to Tambaram with a basketful of mud-crabs to distribute to faculty families. He considered the crabs, which Pulicat Lake has the highest yield of, the “greatest delicacy” on his menu. His Sinhalese wife Savitri’s Ceylon crab curry was always the “top” non-veg dish at dinners he hosted. Today, these mud-crabs are a ‘top’ export.

The national poet

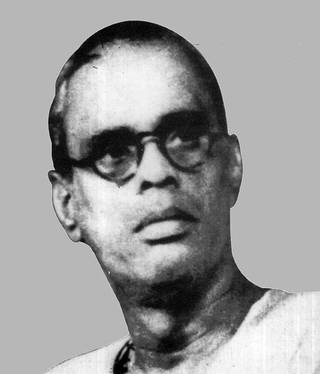

Fair, 6-foot tall, chain-smoking Yogiar was a Gandhian who dressed in silk jibbas and white mull vaishtis and “sang in the voice of Kali”. Devoted to the Devi, he’d compose poetry almost on request but would always say, “The voice is mine/The singer is Kali”. His cornucopia of poetry and prose has been nationalised by Government, but what it’s done with the collection I have no idea.

Yogiar was a polymath, described as a “scholar in English (which he spoke impeccably and accentlessly), writer in Tamil, one-time film director, sometime editor and all-time poet.” He was also a freedom fighter who spent nearly two years in gaol. In prison, Yogiar, author of Mudal Devi, wrote, inspired by a Malayalam writer’s work, his own version of Mary Magdalene. He also translated in Tamil Omar Khayyam’s Rubaiyat and in English a part of Kambar’s Ramayanam, titling it Seetha Kalyanam.

As Editor-in-Chief with India Book House’s publishing division Pearl in the late 1950s, till his untimely death in 1963, he was prolific in translating Tamil and Malayalam classics into English.

A regular reviewer for The Hindu of Tamil and English books, Yogiar would also analyse Gandhi’s and Periyar’s speeches for various publications, often critically. Several of his contrary views helped Periyar re-think his own. As Editor of Pudumai Pithan and other journals — the restless Yogiar kept changing jobs, from journal to journal, business establishment to establishment — he was known for his critiques of films and literature. But as Kannadasan said, Yogiar’s reviews hurt no one nor were they abusive; they only politely pointed out the faults.

Inevitably filmdom beckoned. He worked on seven films. Writing story, dialogue and lyrics for the Ellis Dungan directed Iru Sagodharagal (Two Brothers) got him started in 1936. He then directed some of these, including his own Yogi Films’ Anandam (1941) for which he did everything but act or shoot. National poet Yogiar may have been, but his passion was Mother Tamil, which he once lauded: With the Comorin her lotus feet,/ Seven Hills as her golden crown,/ The bubbling Kaveri as her waistbelt,/ And the Three Seas paying obeisance,/ Holding the tall peaks of Vindhyas as Sceptre,/ Having Lanka as a blooming daughter,/ Our deity is Mother Goddess, / And our home is the land of Tamil, / The evergreen Maiden.

The chronicler of Madras that is Chennai tells stories of people, places, and events from the years gone by, and sometimes, from today.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Madras Miscellany> News> Cities> Chennai / by S. Muthiah / December 11th, 2017