As the new year gets underway, it’s time what is now rather unrecognisably being called Vivanta by Taj Connemara begins thinking of how to celebrate its 125th birthday on November 27th and to tell everyone that it is the oldest Western-style hotel in South India still-in-business. Its roots, however, go back to even before 1890.

On the Connemara’s site by what was once called the Neill statue junction there was one of Madras’s earliest Western-style hotels, The Imperial, dating to 1854 and long pre-dating the controversial statue to one of the hangmen of the Great Revolt, Gen. James Neill. An 1880 advertisement referring to the Neill Statue location and the date of establishment has its proprietor T. Ruthnavaloo Moodeliar stating that the “Premises consist of a large Upstair House, detached Bungalow, and Bachelor’s quarters” and urging the public to take a look at the hotel’s “Testimonial Books, which certify to the respectability, comfort and good management of the Establishment.” The buildings referred to were no longer those of John Binny, who sank the roots of Binny’s in 1799 after having been in the Nawab of Arcot’s service from 1797 and from whom he had acquired the property. He lived in this garden house till his death in 1821 after which Binny’s sold the property which eventually came into Ruthnavaloo Moodeliar’s hands.

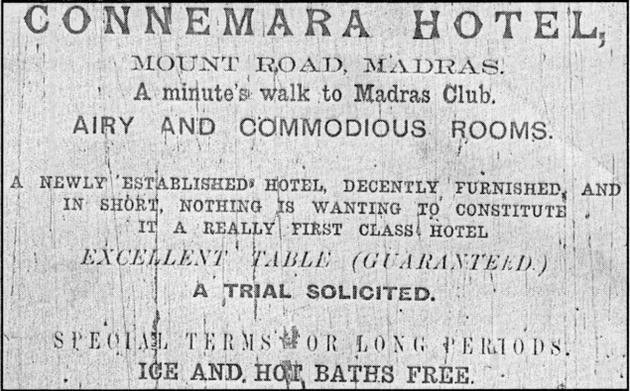

Somewhere along the way, The Imperial became the Albany, no doubt the name given to it by a new lessee, and then became the Connemara, the name given to it in 1890 by the brothers P. Cumaraguru and Chokalinga Mudelly who took it on a three-year lease. On December 3, 1890, the brothers “solicited” in an advertisement a trial of their new establishment which was only “a minute’s walk to the Madras Club”. The advertisement (alongside) promised “nothing is wanting to constitute it a really first class hotel” and also “guaranteed” an “excellent table”. Its new name, however, is unexplained.

But The Madras Mail of November 27, 1890, reporting on the opening of the Connemara wrote, “In the dim and distant future when people as yet unborn will bend their steps to Chennaipatnam (a remarkably prophetic quote, your columnist thinks) and seek boarding and lodging at the ‘Connemara’, they may be induced by a laudable curiosity to enquire ‘why does this hotel bear the name of a district of the County Galway in Ireland’. Then will the phenomenally well informed, old inhabitant make reply, and enlarge on the halcyon days when my Lord Connemara ruled the land, lived his little span, and then passed away, neither unregretted nor unsung. Well may his Excellency exclaim with the bard, when he reads the legend in large characters that spans the chief entrance to the Hotel referred to:

‘Nor fame I slight, nor for her favours I call,

She comes unlooked for, if she comes at all.’ ”

Eugene Oakshott of Spencer’s, bent on expanding his empire, acquired the hotel on April 23, 1891 and let the lease to the Mudelly brothers run till its end in 1893 when he got his partner James Stiven to run the hotel. At the time garden houses were the spaces used for hotels. Stiven reconstructed the Connemara and in May 1901 it became Madras’s first hotel to be housed in a building specifically built to be a hotel. On July 1, 1913, Eugene Oakshott’s sons Percy and Roy sold the hotel to Spencer’s in whose hands it still remains a hundred years later, though it is managed by The Taj Group.

*****

Of shells and bombs

At a lunch the other day, my neighbour at the table wanted to know whether I learn something new from the readers who write to this column. I told her that I learn something new every day not only from all those who keep the postman and other means of communication busy but from the journals and other publications I receive as well as the places I visit.

I mention this because of something I learnt from a picture of an exhibit in the Fort Museum that I found in a publication I received recently. For years I’ve been visiting the Fort Museum but till now had not really read the information on two brass plaques there. After reading the first few lines on the first plaque, I had skipped the rest thinking that all of it had to do with the shelling of Madras by the SMS Emden in 1914, a subject which I had read much about. But to my surprise the picture I looked at the other day showed the second plaque providing me a more positive answer to a question I’ve often been asked about whether Madras had been bombed by the Japanese during World War II and to which I always tended to give uncertain answers. And there the answer has been all these years in the Fort Museum. Yes, Madras was bombed — not in 1942, as all who’ve asked me the question tended to believe, but in 1943. That raises a mystery or two, which I’ll come to in a moment.

First the two plaques. One is titled ‘Bombardment of Madras’, the other ‘Bombing of Madras’. The first displays a fragment of a ‘shell’ fired by the Emden and presented to the Museum by V.K. Ratnasabapathy of Bangalore and the other displays a fragment of a ‘bomb’ — all the terminology, I note, is perfectly correct — “dropped by a Japanese fighter craft on Madras on 12th October 1943…” It was presented to the Museum by A.V. Patro, Commissioner of Police, Madras. And it can’t get more official than that.

But despite the official seal to the information there remains a mystery or two. Few fighter aircraft carried bombs during World War II. Fighters were also short range aircraft, particularly if it was a Mitsubishi Zero (or its seaplane version) as many surmise it was. So did it come from an aircraft carrier? But by 1943, the Japanese had virtually quit the Indian Ocean. So where was there a carrier? Answers from anyone?

******

The Boddam statue

Justice Hungerford Tudor Boddam, a Puisne Judge of the Madras High Court (1896-1908), is one of the few British High Court judges to have a statue of him raised in the city. And I have often wondered why, particularly as he was said to be a mediocre judge. I recently came across an account which might explain why he was so privileged. Apparently he took a considerable interest in the activities of the Madras Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA). This included getting its handsome building on Vepery High Road built and inaugurated in 1900 and persuading leading local citizens like Raja Sir Ramaswami Mudaliar, Lodd Govindoss and G. Narayanaswami Chetty to get involved with the Society’s activities. The statue was first raised near the Willingdon (now Periyar) Bridge on Mount Road but was later moved to Napier Park from where it’s gone into seclusion till the Metro authorities keep their promise and return it to Napier Park once their work in finished.

A proposal for such a society was first discussed in 1877 by some of the leading Europeans of Madras, but it was established only in 1881, with the Duke of Buckingham and Chandos its first Patron and Bishop Frederick Gell its first President. It had in its first years an entirely European membership, Indians showing little interest in its activities which focused on preventing the ill-treatment of animals and improving the conditions under which they were maintained. It was Boddam’s efforts that led to Indians joining the Society from 1903. By then Boddam had got Raja Venugopala Mudaliar to fund the Hospital for Animals that stands in Vepery in the donor’s name.

The society had no plenary powers during the first years of its existence. In 1894, Government conferred on it plenary powers and the SPCA was granted police powers to charge persons ill-treating animals. Starting with action it took when, in 1936, 23 goats were slaughtered in a mutt in Kumbakonam to the chanting of mantras and the flesh offered to the deities, it did much to bring down animal sacrifice in the State.

Boddam was also responsible for persuading the local citizenry to found a pinjrapole. The same citizenry, mainly the Gujaratis of Madras, were possibly those whose “subscription” made possible the 1911 statue.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Features> MetroPlus / by S. Muthiah / February 08th, 2015