Marking its 175th year in muted fashion this year is Presidency College, the oldest college in South India and the seed from which Madras University grew. But its early history has always left me with a question or two and I wonder whether some academic will shed some brighter light on those rather murky beginnings.

It was in March 1835 that the Government of India stated that “the object of Government ought to be the promotion of European literature and sciences among the natives of India.” It was an affirmation of Macaulay’s Minute on Education. But none of the Presidency governments knew quite what to do with this statement of policy. Of suggestions there was no shortage, but while Calcutta and Bombay did get around to action on some of these suggestions, Madras kept a debate going till there arrived a new Governor, Lord John Elphinstone, in 1838. To him George Norton, then the Advocate-General, and a few other eminent personalities presented a petition in November 1939 signed by 70,000 ‘native inhabitants’ seeking institutions of higher education.

Their petition read in part, “We see in the intellectual advancement of the people the true foundation of the nation’s prosperity… We descend from the oldest native subjects of the British Power in India, but we are the last who have been considered in the political endowments devoted to this liberal object…Where amongst us are the collegiate institutions which, founded for these generous objects, adorn the two sister presidencies?” The petition also promised that the citizenry would also gladly, “according to our means”, play a role in establishing such institutions if Government gave the lead.

A month later, Elphinstone responded positively with a proposal which is still what confuses me, even if it finally resulted in the birth of Presidency College. He proposed establishing a “collegiate institution, or a ‘University’” with two departments: A high school offering English Literature, a Regional language, Philosophy, and Science, to prepare students for the second department, the College, which would provide instruction in the higher branches of these subjects. A University Board, headed by Norton, was appointed in January 1840 to implement this proposal.

My confusion arises when I wonder whether there were no high schools before this — Madras history is full of schools of different types from at least 1715 and couldn’t they have years before 1840 been developed into high schools? Even as we wonder over this, there comes another poser. The University Board gets down to work and, believe it or not, starts a preparatory school! This school, started in Edinburgh House, Egmore, and later moved to Popham’s Broadway, was meant to prepare students for the High School! What were the other schools in Old Madras doing?

The High School opened its doors on April 14, 1841, in D’Monte House, Egmore, where the Chief Magistrate’s Court now is. Elphinstone, inaugurating the School, told the gathering, which included the School’s first 67 students that they were “witnessing the dawn of a new era, rather than the opening of a new school.” After studying English Prose and Grammar, Arithmetic and Algebra, Moral Science, History, Mechanics, Natural Philosophy, a vernacular and, in due course, Political Economy, the students graduated as ‘Proficients’. But what did they do for a degree?

Eyre Burton Powell, a Cambridge Wrangler, was appointed Headmaster and in 1853 saw the High School elevated to collegiate status. Two years later, in 1855, he became the first principal of the school that had attained collegiate status and which had been named Presidency College. But with no University in sight — The University of Madras was still two years away — where were the students getting their degrees — if any — from? Another mystery. The College moved to its new buildings on the Marina in 1870-71 by when its students were getting University of Madras degrees.

I don’t know whether a centenary or an earlier jubilee history of the College was written providing answers to all these strange goings-on in the early years of the institution. If not, one should be written now to explain why a major policy decision had to be taken to establish a prep school and a high school and how a college was founded with no University affiliation. Or perhaps someone will provide answers before a book is even thought of.

/ The Hindu

… And a 125-year-old one

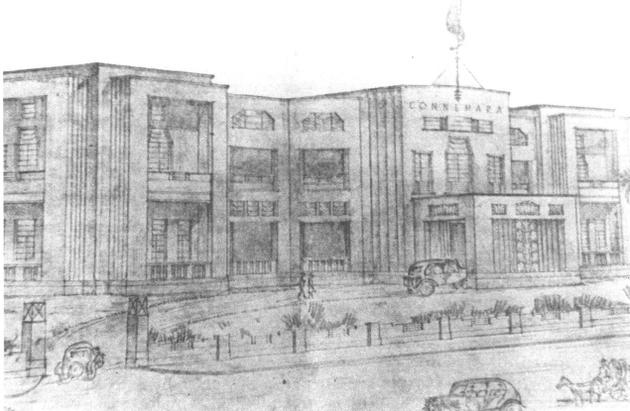

To mark its 125th year as the Connemara Hotel — without seeking to celebrate the years before that when it had been a hotel under different names — this landmark institution in the city is soon to start a year-long refurbishment and when that’s over I hope it will just be the Connemara again. I also hope it will then commemorate someone who has long been forgotten by it — Eugene Oakshott.

The hotel has a Wallajah Room and an Arcot Room recalling the name of the Nawab, as well as that of his fiefdom, on whose once-upon-a-time land-holding the hotel came up. It also has a Binny Room, recalling the owner of a property successive hoteliers took over before it became the Connemara’s, but nowhere in the hotel is there anything named after the man who took over in 1891 the hotel that had been renamed the Connemara in 1890.

Eugene Oakshott was the boxwallah who took over in 1882 a small store called Spencer’s on Mount Road and by 1895 moved it into a palatial home further up the road and got it on its way to becoming the biggest retailing empire in Asia. He then bought for himself the neighbouring Connemara on the advice of a colleague James Stiven, who became a partner in, and General Manager of, the Connemara. It was Stiven who took the first steps towards making the Connemara what it became from the 1930s, the leading hotel in Madras till the 1970s.

How about an Oakshott Hall and a Stiven’s Bar to remember them both when the hotel opens in its new avatar next year?

When the postman knocked…

* Recalling the founding of Vidya Mandir, (Miscellany, March 14) C.L.R. Narasimhan, an old boy of Rosary Matric, remembers what a shock it was to parents like his who found their wards being suddenly asked to leave Rosary in the middle of its year when they were in the 4th Class. “It created a lot of consternation among parents, many of whom were active members of the Mylapore Ladies Club.” The concerted reaction of many such parents, he adds, led to the founding of Vidya Mandir 60 years ago. Nearby St. Bede’s and St. Patrick’s did not offer State Board finals and getting into Madras Christian College High School or Hindu High School was not only not easy but they were quite a distance away. So there was born of the determination of the MLC members Vidya Mandir with just one class, Class Four, and two “outstanding” teachers, Ammini, the daughter of noted scholar P.N. Appuswamy, and Stella, who later migrated to Australia.

Narasimhan also points out that there was a time when the Mylapore Ladies Club had an emphasis on sport, Ball Badminton being the most popular game. The five-a-side game played with a fluffy yellow ball is little heard of today, but till the 1960s it was one of the most participated in sports activities in South India. Shantha Narasimhan, my correspondent’s mother, was a regular member of the MLC team, which was one of the strongest teams in the city. Noteworthily, all its members played in nine-yard sarees! “It was comfort personified, my mother used to insist, whether playing badminton or tennis or rowing in the Kodaikanal regattas,” concludes Narasimhan.

* Going past the San Thomé cathedral, on the same side, you cross a narrow lane and then a pair of very impressive gates. To whom do these gates belong, asks G. Shantha. Judging from her description, I think the Church Shantha refers to is the St. Thomas Basilica. In which case, the handsome gates are those of the Archbishop of Mylapore’s Palace. The Palace is on the site of the large garden house John de Monte, a knight of the church, built in 1804. It passed through many hands, including Thomas Parry’s, before it was bought by the Church in 1838. Just before the consecration of the Basilica in 1896, Bishop Dom Henriques da Silva made it his Episcopal Palace. After the Archdiocese of Madras-Mylapore was created on December 12, 1952, its first Archbishop, Rev. Dr. Louis Mathias, had the Palace renovated and considerably expanded over the next year. The handsome gates were made by the Salesian Technical Institute, in Basin Bridge. He even created a museum of Catholic antiquities in the Palace grounds. But this has now been moved to buildings in the rear of the Basilica.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Features> MetroPlus> Madras Miscellany / by S. Muthiah / Chennai – March 26th, 2016